This is part of “The Edges of Southeast Asia” project by Deloitte, the Singapore Economic Development Board and the US-ASEAN Business Council, which shines a light on the bright spots of creativity and innovation in the region. We take a look at emerging 'edges' or customer segments, geographic markets or products that offer high growth potential opportunities in ASEAN.

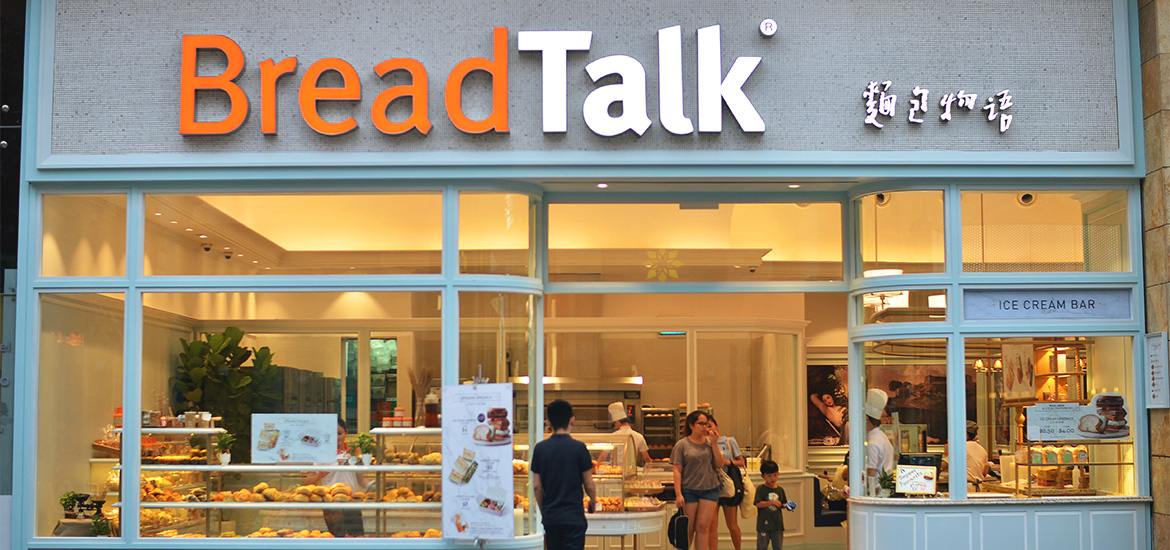

It seems unlikely that putting pork floss on top of a simple white-bread bun could help power a company's expansion to 17 international markets.

But that is what has happened at BreadTalk, the high-growth food and beverage group that sprouted from a single outlet in Singapore's Bugis Junction selling its signature Flosss buns. It has since grown to span 11 food brands, employ close to 7,000 people and open almost 1,000 outlets in ASEAN and around the world.

We believe the BreadTalk story offers lessons for other businesses looking to succeed in Southeast Asia as the region continues its meteoric rise. The 10 nations that make up ASEAN are already home to more than 650 million people and have a combined gross domestic product of about US$3 trillion (S$4 trillion). If these nations were one country, they would be the fifth-largest economy in the world.

They would also be among the fastest changing. The percentage of people in the region categorised as middle-class is expected to more than double from 24 per cent today to 51 per cent in 2030 - or from 135 million people to 334 million people. By 2022, the ASEAN middle class is expected to wield over US$300 billion in disposable income.

Some have rightly observed that the primary defining characteristic of Southeast Asia is diversity. Others have argued that this is essentially another way of saying that Southeast Asia has no defining characteristics. However, one only needs to look a little closer to find that the ASEAN middle class is in fact united by a few key trends.

Global yet local

As companies like BreadTalk understand, ASEAN is not a monolithic entity but a diverse collection of nations, each with its own rich history and culture.

Such successful companies also understand that the region's increasingly affluent consumers want the best of both global offerings and their own unique culture.

For a company like BreadTalk, this means providing a local delicacy in clean, modern and air-conditioned stores, and adapting its menu to suit different markets in the region. It also means creating sophisticated and large-scale regional business systems and supply chains to match local conditions across the diverse ASEAN region and beyond.

BreadTalk is not the only company making global goods and services meet local needs. Mimpikita, which means "our dreams" in Malay, is a fashion label established by a trio of sisters from Malaysia that focuses on high-end "modest" fashion. Their brand made it to the London Fashion Week and has since garnered a large following among the region's Muslim population.

The Global Halal Data Pool - an information repository developed by Serunai Commerce that connects halal suppliers to manufacturers, buyers, and retailers to synchronise the listing of their halal-certified products globally - is another instance of a service tailored to local needs.

Companies outside of Southeast Asia are also looking to put local cultures on the global stage. For example, since 2015, a United States company, 88rising - a new-age media and music company committed to telling an authentic Asian story in an era of digital media - has mentored multiple artists from countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines.

This approach is known as "glocalisation", and holds the key to success for any business looking to benefit from the burgeoning ASEAN middle class. Therefore, it is important for firms to really understand what it means to "go glocal" in ASEAN today. This means looking beyond the big-picture changes in demographics and wealth to consider how factors such as urbanisation, culture and even COVID-19 are shaping the emergence of the region's middle class.

Urbanisation and emergence of the middle class

There is a close association between rising incomes and urbanisation in Southeast Asia. The region's largest cities are the primary drivers of economic growth and home to most middle-class citizens.

Another 90 million people are expected to move to the region's major cities by 2030, and it is estimated that nearly 70 per cent of ASEAN's population will live in urban areas by 2050. Those who are already doing well are expected to become even more affluent, joining the upper-middle class, with its own preferences and aspirations.

However, businesses should not overlook the rapid growth that is occurring in smaller middle-weight cities. Research has shown that more than 200 such cities in Southeast Asia are growing faster than the high-profile capitals such as Bangkok and Hanoi.

Furthermore, these smaller cities are expected to drive about 40 per cent of the region's economic growth from now to 2030. For example, the Indonesian cities of Bandung, Makassar and Surabaya are all growing faster than Jakarta. While these are all places in which the middle class will next emerge, other places to watch are cities benefiting from China's Belt and Road Initiative such as Luang Prabang in Laos and Nong Khai in Thailand, which are creating jobs through infrastructure investments.

Diverse identities

The emerging ASEAN middle class will be embedded in a cultural melee and is enabled by the digital ecosystem. In other words, Southeast Asians will not be a one-dimensional middle-class.

For example, the digital economy enables them to juggle their identities as family members and as micro-entrepreneurs. One can be a full-time parent whilst making money by working as an app-hailing driver with Grab or Gojek or be a student whilst managing home-based businesses.

Southeast Asia also sits at the crossroads between a traditionally Western-dominated Internet, a growing Chinese Internet culture, and its own emerging native online spaces.

Subcultures like those of K-Pop, Japanese anime and even American-led green culture are also influential. People might listen to American pop music on Spotify, use TikTok for both leisure and business, and watch local films on Viddsee, a growing platform for film-makers in Southeast Asia to showcase their works.

With middle-class lifestyles also come middle-class hobbies, which are in turn another facet of one's identity. Leisure and entertainment will be a growing aspect of Southeast Asians' lives.

The gaming industry is exploding in Southeast Asia, with related sales reaching US$4.4 billion in 2019. Moreover, the toys, hobbies and DIY segment saw the fastest growth in online consumer expenditure after groceries, surpassing US$3.6 billion in 2018.

The result is that the ASEAN middle-class consumers are defining and negotiating rich, multi-layered identities that traverse their home and working lives, drawing on cultures from both the physical and virtual worlds.

COVID-19 reshaping the region

It is too early to say what impact COVID-19 might have on these longer-term trends. However, there is reason to believe the pandemic will make it even more important for companies to consider glocalisation and to ensure they have effective digital strategies.

It is widely recognised that the COVID-19 crisis has pushed economic activity online, making the Internet the new competitive battleground for many businesses.

In addition, widespread travel restrictions are forcing people to spend more time in their home and engaging with their local community and culture. This may increase people's preferences for products and services that reflect their local culture, especially those who refer back to simpler times.

Many ASEAN governments have also introduced economic stimulus measures aimed at boosting economic resilience by sustaining demand and consumption within their borders. These include direct income support payments and grants to enable local small businesses to digitise their operations. Taken together, these may further encourage localised production and consumption.

An exceptional place for innovation and business

The growth of the ASEAN middle class presents a significant opportunity for local and global businesses. We are confident that those who take the time to understand the rich and multi-layered nature of the region and act accordingly will be rewarded.

Just as the China-based ByteDance's innovative Tik Tok model of online commercial retail marketing is now being "tested" by Oracle and Walmart in the United States, it would not be surprising to see successful commercial partnerships between global companies and innovative ASEAN businesses like Grab, Gojek, and Lazada to develop new business models and platforms for the region and for global markets.

Moreover, the active participation of ASEAN nations in global supply chains is likely to expand further as new free trade and digital economy agreements come into force across the region.

These agreements should attract foreign producers of goods and services and encourage them to invest in local companies that can innovate to meet the changing needs and tastes of the region's consumers.

This propensity for innovation is one more reason why markets in Southeast Asia with fast-growing middle classes are not just good places to do business today but they are also places that will transform how business gets done tomorrow.

Ambassador (Ret) Michael W. Michalak is senior vice-president and regional managing director at the US-ASEAN Business Council and a former US Ambassador to Vietnam and Apec. Marc Mealy is senior vice-president - policy at the US-ASEAN Business Council.

This article was first published on The Straits Times, and is reproduced with the author's permission.