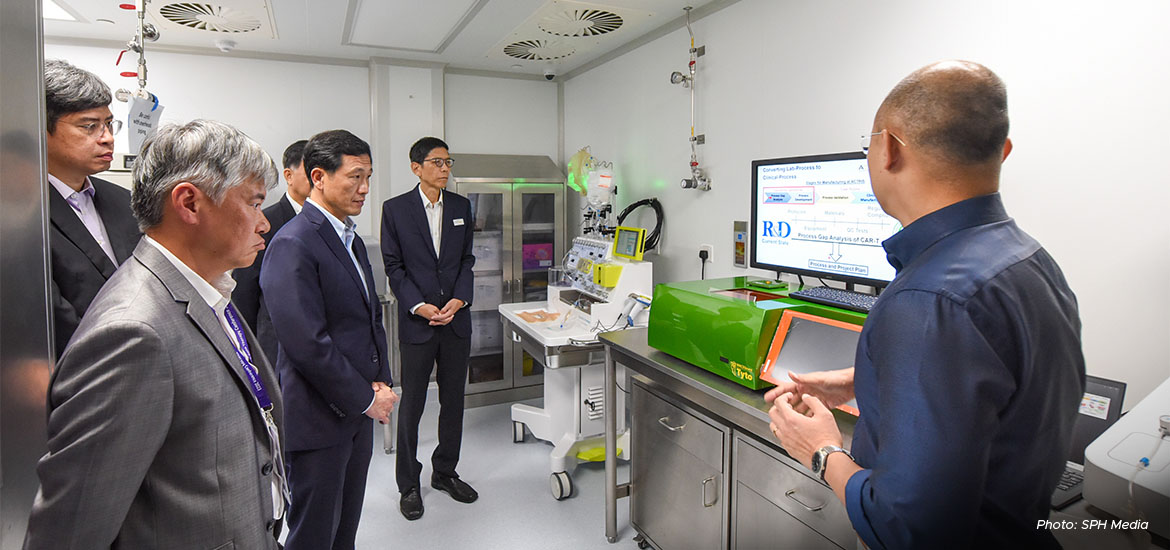

Mr Ong identified several key areas which would allow precision medicine to grow while ensuring safeguards. These include establishing a proper clinical governance framework and setting up legislative safeguards, he said, noting genetic data could be misused by employers to make hiring decisions, for example.

There also needs to be a sustainable way to finance precision medicine, whose costs are “considerably higher than traditional treatments”, he added.

An appropriate financing framework is needed to prevent a schism from forming between those who can afford such treatments and those who cannot.

“I don’t think there is a healthcare system in the world which has found such a solution yet. But given the nature of CGT – relatively infrequent in deployment and high cost – the solution will likely lie in strengthening national healthcare insurance,” Mr Ong added.

Cell therapy refers to the harnessing of living cells to treat diseases such as cancer and autoimmune disorders.

Existing cell therapy treatments have largely targeted blood cancers like leukaemia and lymphoma. Use of the technology has been studied in treating solid cancers – like cancers of the breast, lung and liver – as well as autoimmune and infectious diseases.

While these cells are typically harvested from patients, a two-year trial at the National University Cancer Institute, Singapore is testing the use of white blood cells from healthy donors in treating cancer.

How are the cells obtained?

T-cells are part of the immune system and chimeric antigen receptors (Car) are proteins. In Car T-cell therapy, blood is collected through a process called apheresis.

This involves drawing the blood from the body, passing it through a machine which separates the T-cells and returning the remaining blood to the body.

Car are added to the T-cells and reprogrammed to target cancer cells.

How are the cells introduced to the body?

The patient will have a brief course of low-dose chemotherapy, which improves the chances of the body accepting the new Car T-cells. These Car T-cells are infused into the patient in a process similar to a blood transfusion.

The genetically-modified cells are able to recognise and attach to antigens – proteins found on tumour cells – helping the body kill these tumour cells.

The patient may experience some side effects for a month and the immune system may take several months to recover.

Who can get cell therapy?

In Singapore, Car T-cell therapy is available to some patients up to the age of 25 who have relapsed or not responded to therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, as well as some adults with certain types of lymphoma who have relapsed or not responded to initial treatment. Those with other types of cancer may also have Car T-cell therapy as part of a clinical trial.

Source: The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.