Founder of GlobalSouthTech, Adrian Avendano, shares the different local user behaviours and problems, as well as key barriers to entry and regulatory hurdles to understanding South-East Asia's tech ecosystem.

The ecosystem for startup and tech entrepreneurship in South-East Asia has grown substantially in the past few years. In 2017 alone, funding for South-East Asian late-stage startups captured US$7.86 billion (S$10.8 billion) from investors. The region has dramatically outpaced the rest of the world in per capita GDP growth since the late 1970s, and income growth has remained strong since 2000. Consumers are increasingly moving online, with a mobile penetration rate of 133 per cent and internet penetration of 53 per cent across the region.

However, to scale effectively in this region, founders need to be acquainted with different local user behaviours and problems and identify some key barriers to entry and regulatory hurdles.

A different market

The era of “If you build it they will come” by operating only in tech hubs like Silicon Valley, New York, London, Berlin or any other tech hub alone is certainly over. The tech sector now requires a more nuanced understanding of users from different nations—especially in emerging markets—and how they use and value technology in completely unique ways. A clear challenge for many tech companies and entrepreneurs lies in understanding the different cultural and economic nuances from each country or region and, at the same time, resolving major problems for hundreds of millions of people. We conducted interviews in nine different countries in South-East Asia to understand some of these nuances and challenges.

To help conceptualize the South-East Asia region as one larger tech market, four key points emerge from our interviews. These points will also help to navigate this unique region, generate more successful cross-border expansions, build partnerships, and get investments in the region.

- Shared problems across the region

Mobile-first and mobile-only is a key principle to understand. Smartphones are the very first personal computers for many in Southeast Asia and other emerging markets. As one interviewee explains, in Myanmar alone, people leapfrogged from basically using nothing to a 90 per cent mobile penetration. Similarly, smartphone adoption in 2020 is expected to hit 67 per cent in Indonesia, 71 per cent in the Philippines, and 73 per cent in Myanmar. While it is clear that technology will provide important solutions to local problems, key infrastructure is severely needed and just starting to develop in many of the developing nations.

Some areas to think about are:

- Healthcare and micro-benefits that accrue over time, as commissioned work will increase and talent will be allocated in distributed locations

- Currency volatility in South-East Asia is high, and alternative stores of value will grow in the form of altcoins and cryptocurrencies

- Last-mile logistics will be key, as e-commerce user bases will keep growing and consumers will demand instant delivery services

- Financial inclusion for the unbanked and developing blockchain-powered applications for trade finance, cheap and secure transactions, remittance, and micro-loans

- B2B solutions and SAAS models that make sense for big conglomerates

- Off-grid power and educational technology solutions for the “unconnected”

- Talent pools and solving the tech talent crunch

Our findings show that there is a pervasive stereotype toward many countries in South-East Asia that there is a fundamental lack of tech talent. However, this couldn’t be further from the truth. According to one interviewee, it is all about matching what one wants to build with the talent pool in a specific market. In Cambodia, for example, one may not find AI experts very easily, but there is an abundance of app and e-commerce site developers. Meanwhile, many corporations such as Samsung and Nidec are moving their R&D centres to Vietnam due to the significant pool of talented developers available.

Singapore aims to add 1,000 fintech jobs every year, and Taiwan has a legacy in the hardware industry with an abundance of hardware and software engineers coming from their universities—as 25 per cent of all their degrees are in engineering. This talent could be leveraged substantially for South-East Asia. Thailand also has a great pool of web designers. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, some tech start-ups are solving the tech talent crunch by investing in skilling up their engineers in data science and AI by themselves. - Shared regulatory issues

The startup ecosystem has been growing so fast that most governments in South-East Asia lack legal frameworks for companies to operate efficiently. For example, Vietnam is a new market economy, and the right frameworks to invest in startup companies are nonexistent. The same situation goes for the Philippines regarding investment frameworks, but its government is seriously looking into charting regulations and how they apply to SMEs and startups. Therefore, many startups from the region choose to incorporate in Singapore as an alternative. Taiwan, on the other hand, is launching strong deregulation efforts and creating a string public and private partnerships through Taiwan Tech Arena and with the launch of the startup visa that is possible to get within four to six weeks.

In Cambodia, as a few of our interviewees explained, there are issues stemming from a complete lack of formal regulation. While this makes it easy and cost-effective to open an office there, the lack of regulation encourages ambiguous interpretations that could lead to corruption, inefficiencies and red tape. The result is a lot of wasted time and resources figuring out how to comply with this red tape and make the process smoother, which can ultimately kill margins. - The distributed model for building a tech startup

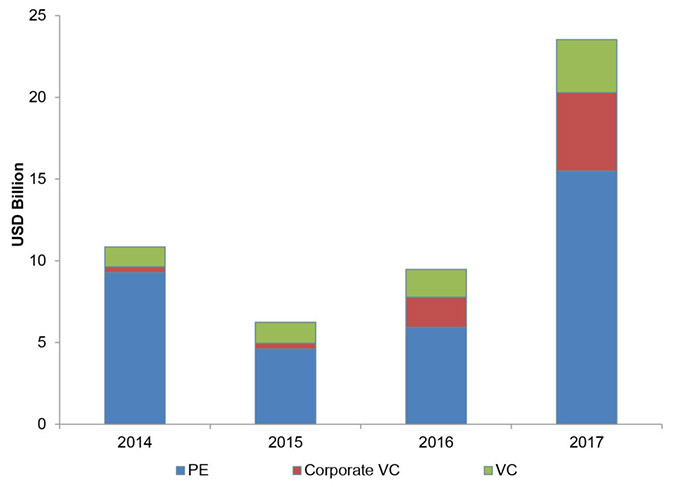

To succeed as a tech startup, many key resources, mentors and partnerships are needed—and are impossible to obtain from one country alone in South-East Asia. Therefore, startups need to leverage several countries at once. For instance, total private equity and venture investments in Southeast Asia stood at US$23.5 billion (S$32.2 billion) in 2017, and in the region, most of these funds are based in Singapore.