Investments surged after a spike in the demand for electronic goods during the COVID-19 pandemic made the industry realise that it needs to add more production capacity.

Even after that global electronics demand eased, amid a glut of inventories, the rising production of electric vehicles and solar panels and the recent red-hot demand for chips needed to power artificial intelligence (AI) applications have kept the industry on its feet.

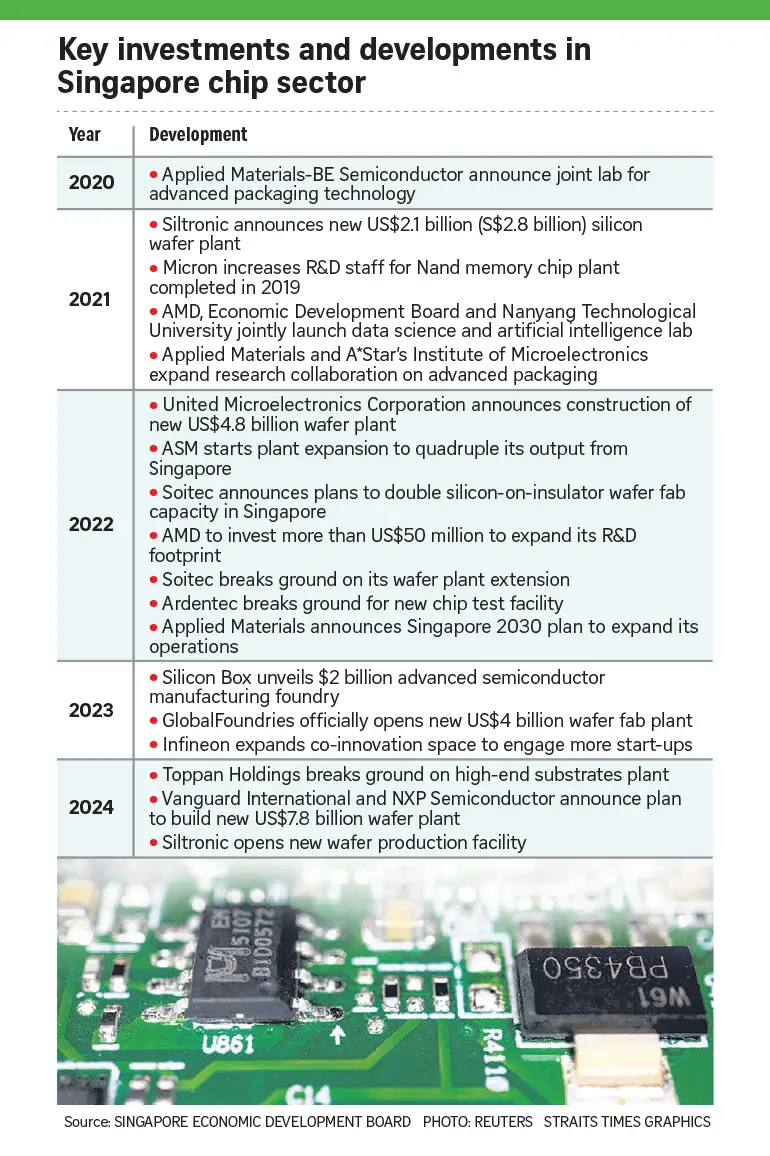

In Singapore, the past two years have seen the announcement of several investment commitments. New investments are pouring in even as some of the companies are just beginning to start initial production.

In June 2024, Vanguard International Semiconductor – an affliate of Taiwan’s TSMC, the world’s largest contract chipmaker – said it will invest US$7.8 billion (S$10.5 billion) together with leading European chipmaker NXP to build a new chip foundry here.

The joint venture, named VisionPower Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, will start making semiconductor wafers in 2027.

It follows a similar manufacturing facility here worth US$5 billion announced by Taiwan’s United Microelectronics Corporation in 2022 and expected to begin operations in 2024.

Analysts such as Mr Justin Feng, HSBC’s Hong Kong-based Asia economist, believe that more foreign investments are likely to follow as the global semiconductor industry, which is now in the crosshairs of US-China tensions and subject to rising tariffs, export controls and even critical mineral restrictions, seeks to de-risk its supply chain.

“The largest eventual beneficiary of Asia’s supply chain reconfiguration could be ASEAN,” said Mr Feng.

He added that Singapore and Malaysia are the only two ASEAN economies with significant chip-manufacturing capabilities.

Both countries were among the early recipients of investments from US chipmakers, which in the 1960s started to offshore parts of their production process to Asian economies – including Hong Kong and Taiwan – with lower labour costs and sufficiently skilled workforces.

Over the past two decades of globalisation, export-led industrial policies, infrastructure investment and domestic innovation promotion, mainland China, Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, and Malaysia have cemented themselves as semiconductor-exporting powerhouses.

“However, a continuation of these macroeconomic trends no longer appears so certain,” Mr Feng said.

He noted: “To succeed in the post-pandemic global economy, Asian chipmakers must grapple with geo-fragmentation, industry overcapacity, and advancements in AI applications.

“After all, these developments have the potential to structurally alter Asia’s semiconductor supply chains and change the trajectories of chipmakers across the region.”